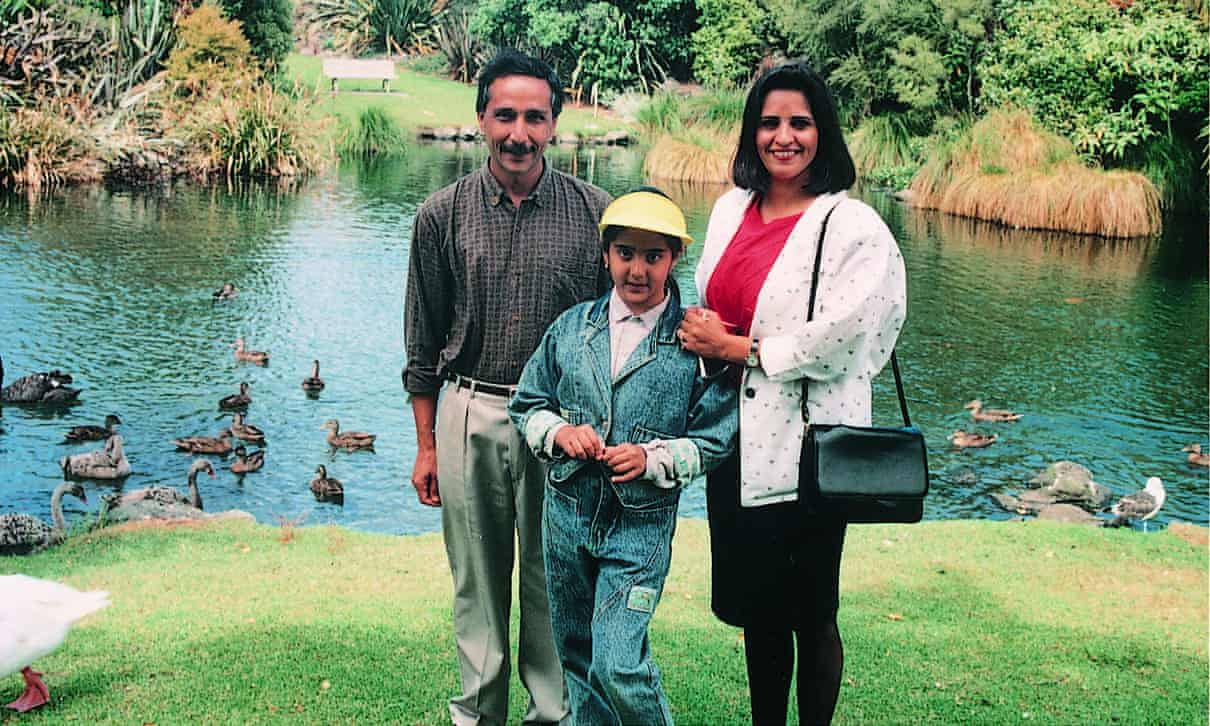

Golriz Ghahraman: 'I feel such sorrow when I imagine my parents' fate'

The Iranian-born New Zealand MP describes a ‘central heartbreak’ of being a migrant child in this exclusive extract from her book Know Your Place

What I noticed and still find painful is that my dad lost his keen, well-known sense of humour. In Iran, he was known as the funny one in his circle. He would do hilarious impersonations of his self-important Dervish uncle for his cousins during late-night sessions at our house. I remember them all doubling over in laughter. He came up with witty nicknames and taglines for every situation.

The dark developments in Iranian society or politics would turn into tragicomedies, a survival tool that made him the centre of attention. These would become ongoing insider jokes in his circle. He was always hilarious for us kids, too. He joined in on our games, took on funny characters, put on funny voices and made us laugh till we had tears rolling down our faces. I was so proud of having the cool, fun dad. After we moved, he was still very funny, but, other than my mum and I, no one around him could tell. Humour doesn’t translate, so he mostly stopped trying.

My mother was an educated, politically minded woman, deeply into literature, involved in women’s issues and passionate about her chosen field, psychology. Suddenly, her university degree, like Dad’s, was unrecognised. Decades later, when she finally had the time and facility, Mum went through the process of having her psychology degree officially converted at the University of Auckland. She was interviewed by a panel, after which they granted her an equivalent degree. By then, life had moved on so far that she couldn’t really face retraining as a clinical practitioner or going back for a master’s degree.

Academia had been her dream. She had dreamed of eventually becoming a professor, of teaching and writing. But the language barrier meant she could not interact with her peers in a way that reflected any of this.

For many years thereafter, my mother would say the hardest thing for her was that she couldn’t make friends by sharing political discourse or having discussions about literature. She would meet people who very likely had read the same books, but for years after we moved, she couldn’t convey the complexity of her thoughts well enough in English to form bonds based on any kind of social analysis. She had to resign herself to interacting as a woman with a keen interest in cooking and gardening, at best talking about simple family issues and sharing everyday advice.

Witnessing that change in our parents is probably a central heartbreak of our shared experience as migrant children, at least for those of us old enough at the time of the change to still remember what they were like before. I noticed my mother smiling more. Smiling all the time, in fact, which translated well in the people-pleasing world of retail and hospitality, where she ended up for the rest of her working life. My dad adopted a slightly bewildered, wide-eyed expression, which went with perpetually asking people to repeat what they were saying. He began to bow his head a lot. Some instinct told him to appear subservient, to be less of a threat.

When I think about it now, I’m breathless with awe at the memory of my parents adapting to their new position in society, rolling with the punches that hit so hard at the innermost sanctum of their beings. I can’t comprehend how they did it.

I try to imagine interesting adults my age, engaged in politics and alternative cultural movements – the people I have in my life now – suddenly becoming impoverished migrants far from home. I don’t understand how rage didn’t overwhelm my parents. It’s the first emotion I think of when I imagine that fate, because the situation that forced them there was so deeply unfair.

The deliberate cruelty of the regime had tipped their lives upside down, as well as the lives of millions more Iranians for generations. That this great loss was still the best option was not fair. The total lack of control would have driven me to a point of perpetual angst. But the deeper emotion – the one that might overwhelm any of us similarly batted about – is sorrow. I feel that now, though. If it was happening for my parents, they certainly never let on.

- Golriz Ghahraman is a member of parliament for New Zealand’s Green party, and the country’s first refugee MP. © Golriz Ghahraman. Extracted from Know Your Place by Golriz Ghahraman, HarperCollins Publishers NZ (RRP $39.99, on sale 16 June)

Source: The Guardian