DID AN AMERICAN BILLIONAIRE PHILANTHROPIST PLAY A ROLE IN THE IMPRISONMENT OF IRANIAN ENVIRONMENTALISTS?

IN SEPTEMBER 2017, a group of Iranian environmentalists working on Asiatic cheetah preservation with the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation felt a pang of alarm. Thomas S. Kaplan, a billionaire precious metals investor then best known for his fine art collection, had just made a surprise public appearance in New York at the annual conference of United Against Nuclear Iran. The Iranian environmentalists were concerned because their group had gotten aid from one of Kaplan’s nonpolitical charities. Now, he was speaking before a group that was extremely hostile to their country.

They were right to be alarmed. Within a few months, several of the group’s members would find themselves behind bars — hit with espionage charges by Iran’s notorious judiciary.

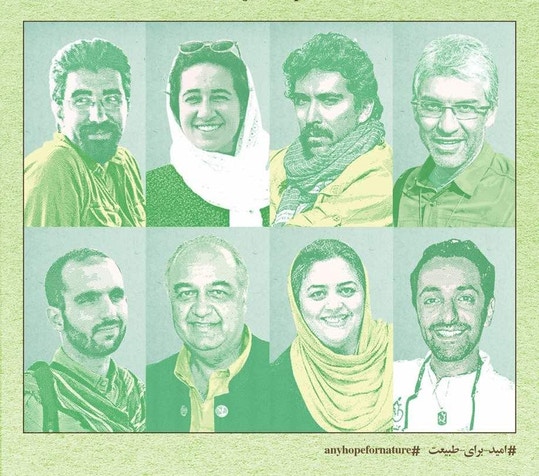

Last week, in a closed-door trial that has been criticized for violating due process standards, eight defendants were found guilty on charges of collaborating with an “enemy state,” according to the Washington Post. Six of the eight were sentenced to between six and 10 years in prison, and sentences for the others remain unclear. The case will now likely head to appeal, where advocates for the environmentalists hope that the verdict will be overturned. In either case, their ordeal seems nowhere near its end: The guilty verdict looks to be just another waypoint in a saga that began two harrowing years ago.

Kaplan’s ties to United Against Nuclear Iran had apparently not been clear to the environmentalists until his 2017 appearance at the conference. Founded in 2008, UANI, as the group is known, is a hawkish advocacy group that led the campaign against the Iran nuclear deal and promotes aggressive U.S. policies toward Iran. Though Kaplan’s ties to UANI were known, they had not been widely publicized. But at the group’s confab in 2017, held at the swanky Roosevelt Hotel in Manhattan, Kaplan publicly discussed his role as one of the organization’s major funders.

In a short speech introducing a panel of speakers — including former CIA director and U.S. military commander David Petraeus, former Saudi intelligence chief Prince Turki al-Faisal, and former U.S.-Middle East peace negotiator Dennis Ross — Kaplan compared contemporary Iran to the expansionist empires of Persian antiquity. In his remarks, he colorfully described the country as a “reticulated python” devouring the other countries of the Middle East. He further suggested that Iran’s Shiite Muslim beliefs led it to pursue a strategy of “taqiyya,” or religious dissimulation, allowing it to conceal its true imperial aims.

The gathering was a shot across the bow of Iran’s leadership, coming less than a year after Donald Trump was elected president on a promise to get tough against the Islamic Republic. Appearing at the UANI event was a significant political coming out for a wealthy philanthropist like Kaplan. His support of a group pushing confrontation with Iran suddenly put him at the heart of one of the most sensitive foreign policy issues in the United States. But inside Iran, Kaplan’s speech sowed distress among a group of people who had nothing to do with his high-stakes game of geopolitics.

While the Iranian government bears ultimate responsibility for its actions against the environmentalists, the story of their arrest, detention, and prosecution suggests that political speech made on the other side of the world can have a potentially dangerous ripple effect.

“People do not understand the impact that their reckless words can have on the lives of people on the other side of the world,” said Ramin Seyed-Emami, whose father, Kavous Seyed-Emami, died behind bars shortly after being taken into Iranian custody in the case. “They can do serious harm to people living in very delicate circumstances in Iran.”

AN ORGANIZATION FOUNDED by Kaplan, Panthera supports projects around the world to protect threatened wild cat species. One of Panthera’s many local NGO partners is based in Iran, the small Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation. Panthera had been providing technical support and advice to the foundation for its work on endangered cheetahs. The environmentalists were said to be in constant touch with Iran’s government about the outside help they were receiving.

Shortly after the UANI conference, however, officials with Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation sent Panthera an urgent letter, first reported by National Geographic and obtained by The Intercept. The letter, sent a few weeks after Kaplan’s speech, expressed obvious concern about Kaplan. “A recent speech and various statements by your Founder and Chairman, Mr. Tom Kaplan and a recent article reiterating same, together with his association with the advocacy group, United Against Nuclear Iran has caused us much alarm and consternation,” said the letter from Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation Board Chair Mahindokht Dehdashtian to Panthera president Luke Hunter. (Hunter is no longer with Panthera and directed The Intercept’s press inquiry to the group.)

“His allegations about our country are absolutely baseless and his statements are insulting to our country and its people,” the letter continued. “We are very sorry to see personal politics have a negative impact on conservation, but these are unusual times.”

The comments reflected an obvious attempt by the Iranian environmentalists to distance themselves from a Kaplan-funded organization like Panthera. Sources close to the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation, who asked for anonymity to discuss the matter, as well as former employees with the big-cat charity, say that Panthera never responded to their letter.

The environmentalists’ efforts, though, came tragically late. A few months after the UANI conference, in January 2018, Iranian authorities arrested Morad Tahbaz, the founder of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation, along with eight other conservationists.

The Iranian prisoners have become a cause célèbre among environmentalists, Iranian reformers, and opponents of the regime alike. Their story is one of the politicization of environmental issues — where, for instance, poor environmental management is weaponized by foreign adversaries for propaganda purposes. Yet it is also the story of a billionaire at the center of a burgeoning geopolitical storm. Kaplan’s money has traveled around the world and back, and his political and environmental activism appear to have finally collided.

“While I do not know what has exactly happened to the PWHF environmentalists in prison, I suspect they have repeatedly faced one troubling question during interrogations: ‘why does an American Jewish billionaire, who funds an anti-Iran organization care so much about conserving cheetahs in Iran?'” Kaveh Madani, a former deputy head of Iran’s Department of Environment and now a fellow at Yale, wrote in a Medium post. “Playing reckless political and security games with the environment jeopardizes the sincere and legitimate actions, and even lives of innocent environmentalists.”

The results have been catastrophic for the imprisoned environmentalists. Seyed-Emami, who held dual citizenship in Iran and Canada, died at age 63 in custody at Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison a month into his detention. The government claims the death was a suicide. Shortly after his death, Seyed-Emami’s son Ramin posted a statement to Instagram. “The news of my father’s passing is impossible to fathom,” he wrote. “They say he committed suicide. I still can’t believe this.” Others among the group of detained environmentalists have said they faced mistreatment behind bars.

News of the government’s case has only trickled out from Iranian state media, which reported on allegations that the environmentalists had been helping monitor Iran’s covert military sites. Numerous reports on government-affiliated news websites have tried to tie the environmentalists to espionage and speculated about their relationship with Kaplan himself. The government claimed that camera traps set up by the Persian Wildlife members to monitor cheetahs had been used as part of a plot to gather intelligence on secretive missile launch sites in the country.

Cole Burton, a conservationist at Canada’s University of British Columbia, told PRI this August that it is unlikely such low-resolution, motion-triggered cameras, designed to capture the movements of passing animals, would be a useful tool for gathering such information.

Following their arrests, five of the environmentalists were charged with national security offenses by Iran’s judiciary — crimes that could carry a possible death penalty. Their trial was marred by accusations of torture and failures of due process. At a hearing this February, Niloufar Bayani, one of the detained, rejected the espionage accusations and described torture she claims to have suffered in custody. Bayani reportedly told the court, “If you were being threatened with a needle of hallucinogenic drugs [hovering] above your arm, you would also confess to whatever they wanted you to confess.”

LIKE MANY WEALTHY people with a taste for philanthropy, Kaplan’s money is spread around an assortment of charities. According to its website, Panthera supports projects around the world protecting wild cat species from Latin America to China. There is no evidence that Kaplan’s interest in conservationism ever crossed over with his hard-line geopolitics, or that Panthera’s activities have been influenced by its funder’s political leanings. But to the paranoid, authoritarian security services of a government like Iran’s, any connection between a local conservation NGO and an organization like Panthera can easily look like a conspiracy in the making.

The Iranian government has grounds to view Kaplan as a powerful enemy. UANI’s work goes well beyond advocacy against Iran in Washington. The group’s board includes a number of former top officials from intelligence and national security agencies in the U.S. and Israel. And UANI appears to have a working relationship with the American national security state: In 2015, a federal judge threw out a civil lawsuit against the group when the U.S. government intervened to assert state secrets — a highly unusual step in a civil suit between private parties.

Kaplan also rubs elbows with a laundry list of Iran’s geopolitical foes, particularly officials from the Persian Gulf monarchies. In an article published by a United Arab Emirates-owned media outlet this February, Kaplan described the Emirates and its leaders as “closest partners in more facets of my life than anyone else other than my wife.” The New York Times recently noted that Kaplan — along with former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and French President Nicholas Sarkozy — was a guest of UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, who reportedly funds Panthera, at his annual salon in Abu Dhabi last December.

Panthera itself also has ties to individuals connected with the national security apparatuses of Israel and the United States. The “Conservation Council” listed on Panthera’s website includes David Petraeus, as well as a former official from Israel’s internal secret service, the Shin Bet. Individuals associated with UANI sit on the council, though these affiliations are not listed on the site. Top government officials from the UAE are also listed, including the UAE’s ambassador to the United States, Yousef al-Otaiba, and U.N. Ambassador Lana Nusseibeh. In June, Kaplan signed an agreement tying Panthera to an Arabian leopard conservation initiative founded by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, according to the online news portal Intelligence Online. In 2018, several months after Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered by Saudi operatives close to bin Salman, Kaplan was spotted in the crown prince’s royal box at an automobile race outside Riyadh.

Panthera and Kaplan did not respond to requests for comment about this article. They have never made any public comments about the arrest of their local partners in Iran. UANI did not respond to a request for comment and neither did the Iranian consulate in New York.

Kaplan’s anti-Iran advocacy, meanwhile, has continued apace. At UANI’s September 2018 conference, while the Iranian conservationists languished in jail, Kaplan showed up again. His appearance, dubbed into Farsi by Voice of America’s Persian language service, seemed calculated to provoke. In front of the cameras, Kaplan was presented with a framed Iranian rial, in recognition of his efforts to help devalue Iran’s currency.

THE ENVIRONMENTALISTS’ CASE has become a cause for concern among their colleagues around the world. But the case has also generated anger over the dangerous politicization of environmental issues in Iran and elsewhere. At least one former employee of Panthera, who had contact with the Iranian environmentalists, believes that Kaplan’s decision to mix politics with his environmental interests recklessly endangered Panthera’s local Iranian partners.

“As conservationists, we are focused on our subjects. Regardless of the nature of local governments, we try and work with them to find compromises to get them to enact policies help protect endangered species and the environment,” Tanya Rosen, who worked at Panthera for six years, told The Intercept. “Until recently, nobody really paid attention to the implications of having certain donors.”

During her time at Panthera, Rosen, who headed the organization’s snow leopard program in Central Asia, had contact with the Iranian environmentalists now languishing in prison. She described them as apolitical and passionately immersed in their conservation efforts. Before their arrest, Rosen had been working with the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation to set up a summit focused on protecting Iranian cheetahs.

“With the wisdom of what we know now, looking back at the board of Panthera, you start wondering, ‘Why didn’t you see it?’” Rosen said. “It’s important to realize that nobody in Panthera, not even senior staff, knew about Kaplan’s involvement with UANI. He never talked about it, he never made any disclosure about it.”

The politicization of environmental issues — especially on Iran — has been a project not just of private donors but state actors as well. In recent years, U.S. and Israeli government officials have been increasingly vocal about Iran’s environmental problems, including air pollution and chronic water scarcity. Last year, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu released a video addressed to Iranians impacted by drought. His video also introduced a website designed to offer them tips drawn from Israeli water management practices. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and former national security adviser John Bolton — both vocal enemies of the Iranian government — have also made a point of highlighting Iran’s environmental crises in their public remarks.

Earlier this year, UANI released an extensive report about Iran’s environment, drawing further political connections to the issue.

Expressions of concern about Iran’s environment, coming from individuals and groups otherwise better known for threatening war with that country, puts local Iranian conservationists in a difficult position. By politicizing environmental issues, Iran’s adversaries have made the environment an area of interest for Iran’s opaque and frightening national security state, an environmentalist targeted by the regime in connection with the Panthera case, who asked for anonymity for security reasons, told The Intercept. Environmental NGOs in Iran, particularly those with foreign ties, now face a heightened danger from security services that are emboldened to view their field as a potential avenue for foreign espionage.

For Rosen, her experience with Panthera and its abandonment of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation activists has left a bitter taste. After the arrests, she left Panthera, explaining that she “could no longer work for an organization that doesn’t care about the safety of their staff or their partners.”

Meanwhile, lingering questions remain about how the reckless behavior of Panthera’s founder may have contributed to the calamity that befell the Iranian conservationists.

“This is not just about someone who dislikes a country,” said Rosen. “It’s about someone who is actively funding efforts to affect that country’s politics, while supporting local environmentalists who had no knowledge of his politics.”

Source: The Interept