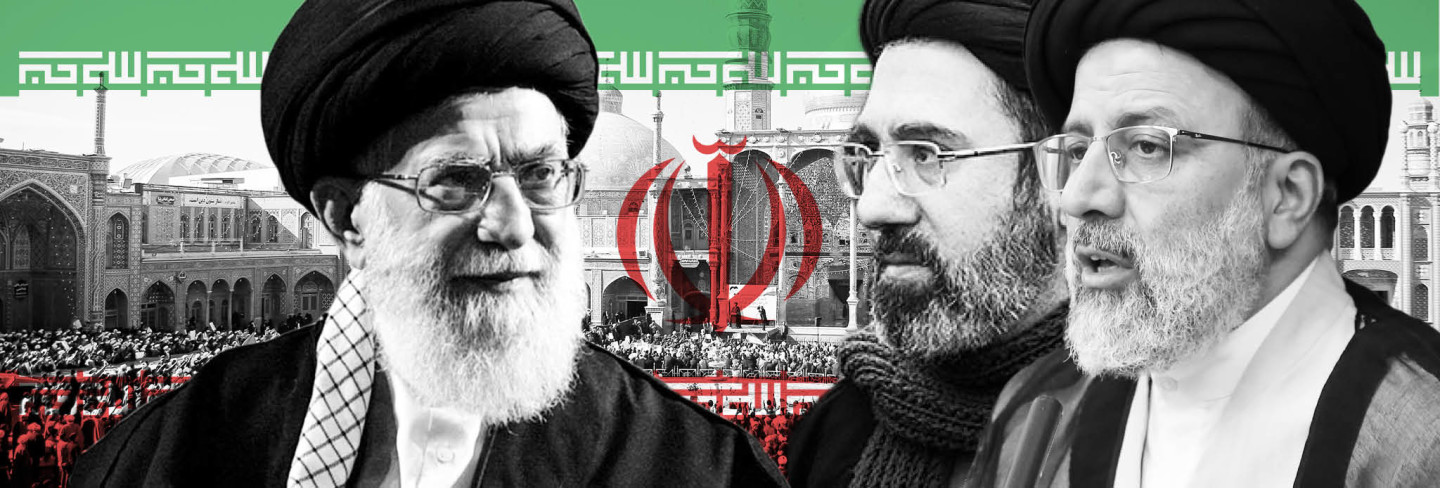

Iran: the unspoken battle to succeed Ayatollah Khamenei

“Bring your people out of darkness into light, and remind them of the Days of Allah,” reads a line in the Koran, Islam’s holy book. This month Iran witnessed two Days of Allah, at least in the minds of the country’s leaders. When Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader, recited the verse to thousands of worshippers last Friday, he reminded them of what he called the blessings brought by two different events over five days. The first was what he described as “the world’s biggest” funeral procession for Qassem Soleimani, a commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps for overseas operations who was killed by the US in Baghdad on January 3. The second was the unprecedented missile strikes on bases housing US forces in Iraq on January 8 by the elite guards force. The top leader’s metaphoric language sent a clear message to Iranian politicians — and to the rest of the world. The Islamic republic, analysts believe, will be even more steadfast in its ideological path at home, while in the rest of the Middle East the guards will promote a fresh radicalism.

Mr Khamenei’s steadfast support for the guards — despite their role in the shooting down of a Ukraine airliner that killed 82 Iranians just hours after the attack on the US forces — comes against the backdrop of a tense battle over who will replace the 80-year-old supreme leader when he dies, a decision that will determine Iran’s fate for decades to come. The choice will depend on where the balance of power lies at that time within the Islamic republic. In recent weeks that balance has further tilted in favour of the guards and their hardline supporters. “We are witnessing the most complicated domestic and foreign games all centred on the issue of succession,” says a reformist analyst. “The [further] empowerment of the guards is a deliberate policy to make them the dominant power so that they can play the main role in the power transition.” According to many hardliners, the events highlight the need to have another pragmatic leader willing to stand up to the US. They play down speculation from reformists that Iranians will want the next supreme leader to be more of a ceremonial post, rather than another all-powerful figure. It was Ayatollah Khamenei — as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces — who authorised the first-ever direct missile attack on US troops which was choreographed to demonstrate Iran’s determination to avenge the assassination of Soleimani without triggering a full-blown war. While no American soldiers were killed, Iran sent messages to the US via the Swiss embassy that it would be the first and last strike if the US administration refrained from hitting back. “Recent developments were like a wake-up call,” says a relative of the supreme leader. “[They] reminded us that the US can get too close to a war with Iran and we need another courageous leader who is able to maintain the country’s stability and power.”

“The country cannot afford to risk a period of trial and error by an inexperienced leader,” he adds. Iran’s theocratic system is based on velayat-e faqih — rule of jurisprudence under Shia Islam. According to the interpretation favoured by hardline politicians, the religious leader may be selected by senior clergy in the Experts Assembly but he is considered to have been appointed by God to rule the Islamic world in the absence of infallible descendants of Prophet Mohammed. Reformist politicians, however, reject this religious interpretation. Instead, they say, a leader’s credentials need public legitimacy manifested in national elections. These different interpretations have been at the centre of Iran’s political infighting since 1989, when Ayatollah Khamenei replaced Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, leader of the 1979 Islamic revolution. Mr Khamenei, who does not have the charisma and high religious credentials of his predecessor, has instead relied on the revised constitution, which gave him an “absolute authority” over all state affairs. Since then, he has helped the guards expand their influence and has turned them into his main arm to exercise power. After recent events, those efforts are now likely to be accelerated, say those close to the regime. “When, God forbid, Mr Khamenei dies, the guards will completely take over the country so that the Experts Assembly can choose a leader,” says a regime insider. “On that day, the guards will be the top force to influence the choice, curb any possible crises and more importantly preserve the territorial integrity.”

The 120,000-strong guards are Iran’s most organised institution, giving them considerable influence over the succession. It also controls a volunteer force believed to be several million strong, adding to its ability to wield that influence. It is not merely a military force. Politicians close to the guards are in various institutions such as the leader’s office, the parliament and the judiciary. The force is believed to have interests in telecoms, trade, petrochemicals and other sectors — something President Hassan Rouhani has previously tried to curb by cutting it out of contracts at state-owned enterprises. It has also expanded its cultural influence, from producing movies and documentaries to contemporary art, and runs a feared intelligence service responsible for the imprisonment of pro-democracy activists and dual nationals accused of espionage. While the guards have some influence over Ayatollah Khamenei, analysts say, they remain loyal to him and respect his final say in all affairs. The next leader, however, may not enjoy so much authority. “The guards are in such a powerful position that no [future] leader will ever threaten their interests,” says Amir Mohebbian, a commentator close to conservative forces in the country. “We are always in an emergency situation and in dire need of stability in a country characterised with historic fears of insecurity.” The elite forces say they observe a constitutional duty to preserve the country’s frontiers but are also responsible “for fulfilling the ideological mission of jihad in God’s way”.

That translates as the guards believing they have a responsibility to galvanise the country against any perceived US threat to Iran and the Islamic world. Hardliners in Tehran fear the ability of Washington to influence Iran’s politics and suspect that Democrats in the US and reformists in Iran have long hoped to resolve historic differences to shape the Islamic republic’s future. When Mr Rouhani signed the deal with the US and other major powers in 2015 to rein in Tehran’s nuclear ambitions, concerns grew within the guards about the potential for a loss of Iranian influence within the region. This was particularly worrisome because Mr Rouhani was re-elected in a landslide in 2017 on promises of getting all US sanctions lifted — an apparent pronouncement of his desire for rapprochement. However, President Donald Trump withdrew the US from the accord in 2018 and imposed even tougher sanctions on the country. Mr Rouhani’s signature achievement was erased and with it any ambitions he might have had of becoming the next supreme leader. “Even if one day we negotiate with the US, the talks will not be with Trump; won’t be strategic [no normalisation of ties] and will be done only by conservatives not reformists,” adds the regime insider. “We need to see changes in [the US] Congress; whether Democrats will pursue a fair policy by which Iran is not under pressure over its missile programme.”

The strategy for now appears to be to play down the tough new US sanctions and mobilise public opinion in the region against Washington and Israel. “The guards’ identity and power is in opposition to the US,” says a reformist politician. “They know that if they take a step back, Americans will look for them in the backyards of their houses. The guards are increasingly into games which are becoming more violent while still smart [in order] not to risk the regime’s survival.” Reformists, however, say the guards are overplaying their hand — both in domestic and Middle East politics, with incidents such as the alleged attack on Saudi Aramco facilities last year — which could provoke further unrest at home. Iranian society is not as obedient as it was three decades ago and potentially less willing to accept a new leader if he is close to hardline forces. Iranians are more educated and have constantly pushed back boundaries, forcing the republic’s rulers to grudgingly allow some opening of the country politically, culturally and socially.

Reformist politicians warn that Iranian public opinion cannot forever tolerate the regime’s risky hostility with the US. The accidental shooting down of the Ukraine International Airlines jet, killing all 176 people on board, is a vivid example. After initial denials, the guards admitted the blunder but only after the US, Canada and Britain had all disclosed details of Iran’s unintentional role in the disaster. The acknowledgment massively damaged public faith in the regime. Thousands of people in big cities, including university students, poured on to the streets, chanting provocative slogans. They called the leader a “killer” whose guardianship was “null and void” and described the guards as a force similar to Isis. Ayatollah Khamenei did not back down, saying these “hundreds” were irrelevant in the face of “tens of millions” who attended the Soleimani funeral. “The Islamic republic can tolerate the foul-mouthed, unarmed opposition and is aware that we are going to see protests more frequently but all are manageable,” says the insider. “We are not going to allow pro-reform groups to use the plane incident to overshadow the gains from the funeral of Soleimani.” The most recent protests follow violent unrest across the country in November, mostly by working-class demonstrators — traditionally backers of the regime. They lashed out at the supreme leader and mounting hardship — including inflation of 38.6 per cent a year and the depreciation of the national currency by about 60 per cent — caused by the US sanctions and massive corruption. The guards brutally suppressed the riots and, according to Amnesty International, opened fire on protesters, killing about 300 people. But many Iranians have lost confidence in the ability of reformists to make any change. Most reformist candidates are barred from running in February’s parliamentary poll, which is expected to pave the way for a hardline victory.

Looking ahead to the 2021 presidential election, some political observers believe the successful candidate will need to be a young, ideologically-motivated hardliner. Potential contenders have not yet become part of public discussions — nor have the names of candidates for the position of supreme leader. Political groups are fearful that their preferred options could become victims of so-called “tall poppy syndrome” if they gain too high a profile at this stage. In private, speculation is rampant about who the guards will favour. Given recent events the odds have shortened on Ayatollah Khamenei’s second son, Mojtaba, though he remains low-profile in his religious and political life. The 51-year-old teaches at a senior level in Qom, the centre of learning for Shia Islam, giving him the status of a ranking cleric necessary for the supreme leader role. Thanks to a mindset similar to his father, the relative says, he has good insight into political and military issues and “is into a knowledge-based economy”. “He has good relations with the guards,” the relative adds. “He may not have the authority of his father, but the guards cannot dictate to him.” The regime insider plays down perceptions that such a choice could make the Islamic republic look like the hereditary monarchy that it ousted more than 40 years ago.

Another potential candidate is Ebrahim Raisi, the hardline judiciary chief who lost the 2017 presidential election to Mr Rouhani and has since campaigned against corruption. “What determines the choice of a leader will be the costs and benefits of political quid pro quo between various interest groups,” says a conservative analyst, who believes that this will favour the guards. “Political groups and the society should think this wheel will turn in their favour.” The positioning among potential candidates is taking place at a time of change in Qom. The seminaries played a vital role in the victory of the revolution and are now the second most important institution after the guards. However, the most senior clerics in Qom are of advanced ages. Grand Ayatollah Hossein Vahid Khorasani, the most senior cleric, is 99. Others include Lotfollah Safi Golpayegani, 100; Hossein Noori Hamedani, 94; Naser Makarem Shirazi, 92; and Mousa Shubairi Zanjani, 91. While the clergy’s main concerns are over people’s religiosity, which has weakened under the Islamic republic over the past four decades, the guards are determined to be the central ideological and political institution that can choose the next clerical leader to rule Iran and expand influence across the border in Iraq. “Whatever Americans do it benefits us, including their wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and now the killing of Soleimani,” says the insider. “Our country is run by the Last Imam [the Mahdi, believed by Shia Muslims to be missing] who decides about the Days of Allah and will help us choose a great leader when the day comes.”

Source: Financial Times