A Jewish-Muslim Love Story in the Days of the Iranian Revolution

True story of two people with different religions but same Iranian roots is the basis of a new work by a playwright who yearns to bring the culture of Iran to Israeli stages.

A Jewish-Iranian teenager named Leah who lives in Israel in the late 1950s meets Amir, a young Muslim Iranian who is attending the Hebrew University of Jerusalem as part of a student exchange program. Amir is studying the kibbutz model with the aim of implementing a similar project in his country; he even writes his thesis in Hebrew. The two of them fall in love and live together in Jerusalem; subsequently, they move to Paris, marry and have a child.

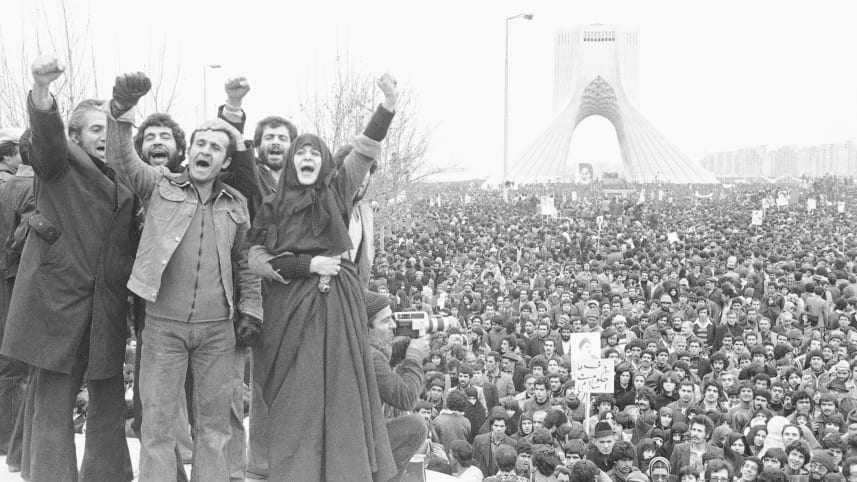

Amir dreams of fomenting change in his homeland. He returns to Iran and becomes a major activist in the Islamic Revolution, which began, like many other upheavals, as a social revolution. Leah goes with him – a Jewish woman in the land of the ayatollahs, who rise to power. After some time, Amir realizes that he has been mistaken in his political aims and he helps smuggle the president of the provisional government to Turkey, dressed as a woman. When arrested for that act, along with 13 others, as well as on a charge of spying for Israel, Amir is jailed for four years in the notorious Evin Prison in Tehran, where he undergoes torture. Leah waits for him, concealing her identity, hardly leaving the house, raising their son. Finally, Amir is released and the family flees to Paris, where they are still living.

This is the underlying plot of a new play by Anna Ben Shlomo, called “Hofesh: Khafeh sho (Shtok!)” (“Freedom: Khafeh sho [Shut up!]”), which will be staged at the Jerusalem Khan Theater on Thursday. And every bit of it is true.

“Throughout all these years I didn’t delve deeply into the Iranian Revolution,” says Ben Shlomo, herself born in Iran. “I felt that it was remote from me. When I started to look into the events that took place there, I found that couple. I went to France to meet them and we spent 11 days together, during which they told me their story. Amir (not his real name) truly believed he was doing the most wonderful thing for his people and his homeland. He and the group he belonged to hooked up with Ayatollah Khomeini in the hope of bringing democracy and equality to Iran. But things turned around very fast. While he was imprisoned his wife underwent much hardship.”

Leah (not her real name) was born in Iran. After her mother died, she came to Israel with her father, and remained there until the age of 15-16.

“Her father didn’t adapt to life here and returned with her to Iran,” relates Ben Shlomo. “She taught Hebrew at an Alliance school there, but after enjoying a life of freedom in Israel, she found it difficult to deal with the rules governing modesty and morality in her homeland and returned to Israel. That’s when she happened to meet an Iranian Muslim and fell in love with him, of all people. Who would have believed that a Muslim Iranian would come here to learn about the kibbutz in order to bring the idea to Iran? Things like that could not happen today – these were revolutions in individual people’s lives.”

Ben Shlomo has also undergone some upheavals in her life. She was born in Iran in 1965 and came to Israel with her family in 1973. “I grew up with a father whose whole life was the theater,” she says. “He wanted to be a comedian and an actor while still in Iran. He came to Israel in 1949 as part of the Youth Aliyah project organized by the Jewish Agency, and went to school on a kibbutz. In the ‘50s he enrolled in a preparatory program run by the Habimah national theater but was not accepted as an actor. I’m guessing it was because of his origins. Because of this he decided to leave and return to Tehran, where he met my mother. He joined a theater troupe that was supported by the shah and they appeared around the country, performing many plays by Western playwrights like Chekhov.

Ben Shlomo’s father, the late Yehuda Mordi, started working for the Jewish Agency in the 1970s, and shortly before the Yom Kippur War the family came to Israel.

“I was 8 years old and was afraid I was going to die,” she recalls. “But right after we immigrated, I took it upon myself to integrate. The first generation often experiences a syndrome of wanting to integrate quickly, to get rid of accents, to erase former identities – become completely Israeli. Over the years I’ve become Israeli, but also Western-oriented.”

Finding her voice

Ben Shlomo studied and taught piano, singing and classical music, but at some point, felt that just as with her parents, the theater was beckoning, so “a few years ago, I decided to do it – say what I have to say on stage.” Moreover, the content she has chosen to present in the world of theater signified a meaningful and big change. She describes the many years, for example, in which she had hidden her Iranian identity, perhaps like Leah who hid her Jewishness.

Ben Shlomo: “When people want to know where you’re from, they ask about your accent, but I’ve been hiding it, even as an older person. It took some time before I could talk about not being born here in Israel. Some of my friends were shocked when they found out; some of them hadn’t known. But when you’re on stage you have to open up about these things. It’s an identity that’s present and you must acknowledge it. I studied theater at Tel Aviv University and I talked there about being born in Iran and about missing it – about the way it tears me up that I can’t visit my childhood landscape. But I couldn’t really let it all out at university. I felt I was being judged and that put me in a place where I couldn’t find myself or my voice. When I graduated, I told myself I was going back to my roots, to Iran.”

The play she wrote is staged by an ensemble called Garu Guru, which aims to bring Iranian culture to the stage, particularly Iranian-Israeli culture. “Garu means ‘group’ in Farsi,” Ben Shlomo explains. The troupe includes Rami Ben-Gur, a member of the Psik Theater (a Jerusalem-based company “with a social conscience), who plays Amir. Other members of the group are guitarist Zohar Elnatan, creative artist Achinoam Aldubi and singer Jeanette Rotstein Yehudian, who plays Leah.

“Jeanette has no acting experience but she was born in Tehran and came to Israel at the age of 14. Her experiences there are expressed on stage in an amazing way during the play,” Ben Shlomo says. “She has a voice that sends chills down your spine, and she related well to the authentic Persian songs that are part of the play.”

The playwright is basically telling the story here of an Iranian Jewish woman who’s given up on life in Israel as well as in Iran: “I bring both stories in parallel. Both of them say: We love our country, our birthplace. The Jewish woman says this about Israel; the Muslim man refers to Iran. Slowly, the story of their love emerges, with its intimacy and longing – the type of thing that is usually kept concealed in Muslim society. Through it one also hears the story of Iran and the revolution there, whose main victims were women. In general, in so-called Oriental societies, women are usually the biggest victims.”

Ben Shlomo adds that her play “blends a true story with my imagined one, along with the issues I researched while writing it – among them identity, religion, dreams, ideals and national loyalties on either side. The biggest question hovering over everything is to what extent must a person make sacrifices for his country, particularly when its political situation doesn’t accord with one’s idealistic expectations.”

At this point in the conversation, she relates how a few years ago she met an Iranian woman at a Turkish airport: “She was very beautiful. We looked at each other and she asked me in Farsi if I was going to Iran. In my excitement I said I was. She was happy and said: Great, we can travel together. I realized that I’d misled her and told her I was Iranian-Israeli. As soon as I said that, she turned around and disappeared. That was hard for me.

“If we [Israelis] continue being a closed society, thinking only about wars, we won’t hear anything about Iranian culture, about people who want regime change. I didn’t want to write a political play, I only wanted to tell a story,” Ben Shlomo continues. “But the issue here is freedom. The [Farsi] name of the play expresses that. It means: shut up, choke on it, die. It’s hard for Iranians to hear that word, but I say, that’s precisely my point: You can’t express yourself or bring yourself to a place that is free.”

Finally, I feel I have to ask how an Israeli Jewish-Iranian woman could be named Anna. “I’m always asked that question,” she says. “Especially because of my darker skin. The thing is that in the ‘60s, my father read the diary of Anne Frank and suggested that a theater group in Tehran stage a play based on her story. The group liked the idea. The play was based on ‘The Diary of a Young Girl,’ in Tehran. My father played a small role in it. The Muslim actors played Jewish roles. I was born when the play made its debut, and he never stopped talking about it all his life. That’s why I had the honor of being named Anna.”

Source: www.haaretz.com